Tim Appleton –

When businessman George Copos sold Rapid București football club in 2013, after two decades in charge, he had overseen one of the most turbulent periods in the team’s long and colourful history. But things have not exactly settled down since his departure…

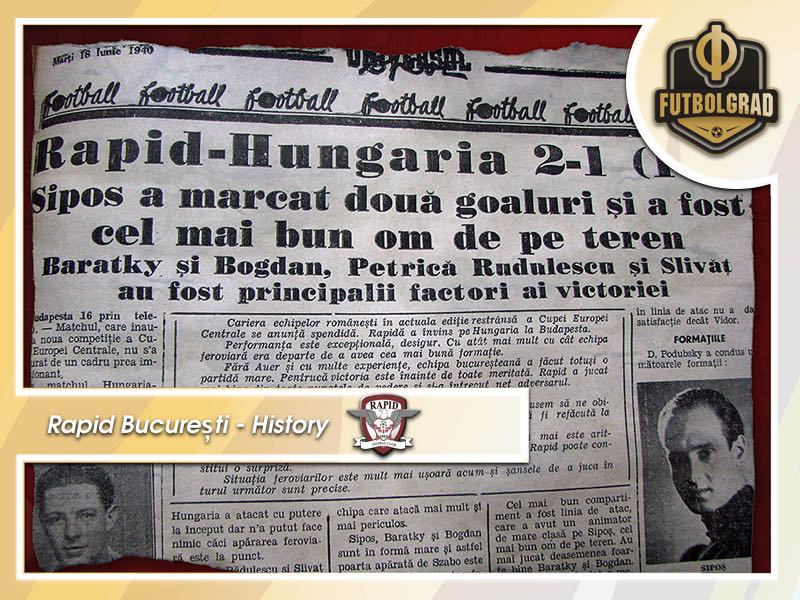

Rapid was founded as CFR București, the railway workers’ sports club, in 1923 and within ten years had become a major force on the emergent football scene in the capital. Their first golden age, which lasted a decade from 1932, saw the club win an astonishing six consecutive Romanian Cups and finish runners-up in the league four times, although the league title eluded them. The club’s earliest heroes date from this period, the most notable being “the Blond Wonder”, Giussy Barátky. An ethnic Hungarian from what is now Oradea in north-western Romania, Barátky played in four cup finals, scoring ten goals, and represented both Hungary and Romania at international level. In June 1940 he led the forward line when the recently renamed Rapid defeated Hungária MTK 2-1 in the Mitropa Cup, becoming the first Romanian team ever to win in Budapest. His team reached the final of that competition; however, due to the war the match against Ferencváros never took place, and Rapid would have to wait almost thirty years for another opportunity to play in European competition.

The post-war regime changed everything, in football as in the country at large: privately-owned clubs, deemed bourgeois and thus incompatible with a socialist nation, were demoted or forcibly disbanded, so that we no longer hear about Carmen, Venus, or Tricolor București. Instead, two new giants, CCA and Dinamo, were created in the capital in 1947-48, as the teams of the defence and interior ministries respectively, on the Soviet model. These received overt state support – regarding both funding and, let’s say, influence – and were often used as proxies for inter-departmental political rivalry. Meanwhile, the railways club, which had survived thanks to its roots as a workers’ association, became the poor relation, the city’s third team. The Rapid supporters’ groups would later become a focus for anti-regime protest, although it is possible that their role in opposing the Ceaușescu dictatorship, which lasted from the sixties through the eighties, has been exaggerated in the intervening years.

A resurgence in the 1960s saw Rapid, after two cup final defeats and three consecutive second-place finishes, finally win their first league title in 1967. The coach was Valentin Stănescu, who would eventually give his name to the club’s Giulești stadium; the captain of the side was defender Dan Coe, who defected to the West in 1980 and was found dead in his Cologne apartment a year later, aged just 40. Rapid supplied five players, including Coe, to the Romania team which took part in the 1970 World Cup in Mexico, the country’s only finals appearance between 1938 and 1990.

Academia Rapid v CSA Steaua at Giulesti (Futbolgrad Network/Tim Appleton)

Two more runners-up spots and two cup wins followed but between 1973 and 1992 came the wilderness years, Rapid enduring several spells in the second division while Dinamo and Steaua (as CCA was now known) enjoyed great success. Then came a shake-up in the way football was run – reflecting a huge instability in the country as a whole in its transition from a planned economy and a restrictive state apparatus, to something vaguely resembling a capitalist system (albeit with ex-communists at the helm). During communist times, football clubs in Romania – as in the rest of the communist bloc – tended to be part of a multi-sport club. In the mid-1990s, many football sections were separated from their multi-sport clubs and sold off to private investors. At this point, Rapid still belonged to the Ministry of Transport. In 1993 Copos, who had made his money from the unlikely combination of bakeries and imported electronics, took majority control of the football section for a reported $800,000. He remained in charge of the club for twenty years, through a spell as deputy prime minister and two lengthy prison sentences for corruption offences. Par for the course for a football club owner in modern Romania.

Rapid in the 1990s – The European return and financial problems

In the first season of Copos’ reign, Rapid returned to European competition after an 18-year absence. Unfortunately, they drew Inter Milan in the first round of the UEFA Cup, and a Dennis Bergkamp hat-trick sent them packing. A few more European nights at Giulești followed, but it was under Mircea Lucescu, recruited by Copos from Italy in 1997, that the team really took off. In 1997-98 Rapid finished second in the league and won their tenth Romanian Cup, against Universitatea Craiova, in front of 65,000 success-starved fans (of both teams). The third golden age of Rapid had arrived!

The following season, defeat in the cup final (to Steaua, on penalties) was balanced out by the league title, sewn up a couple of weeks earlier. Copos was celebrated, somewhat ironically, as the ‘Berlusconi of Giulești’. Nicolae “Nae” Stanciu captained the team; alongside him in defence was Mircea Rednic, veteran of the 1984 Euros and 1990 World Cup. The experience of Rednic’s Italia ‘90 team-mates, playmaker Danuț Lupu and midfielder Ovidiu Sabău, was balanced by talented youth in goalkeeper Bogdan Lobonț, defenders Mugur Bolohan and Adrian Iencsi, and striker Daniel Pancu. Lucescu was poached by Inter in November 1998, and Rednic took over as the coach for a short time.

Greater glories were to come. Another cup was won in 2002, and the next season Rapid topped the table for the whole campaign to earn their third league title. Rednic was the coach and Iencsi captain, while more young players had emerged in the shape of full-back Răzvan Raț, versatile defender Vasile Maftei and forward Daniel Niculae.

After finishing third in the league again in 2005, fans would have expected the usual routine from their UEFA Cup jolly: win the qualifying round and get knocked out in the first round proper. Nobody predicted a record-breaking sixteen-game run in the competition. First dispatching Andorrans and Macedonians, surely title-chasing Feyenoord would be too strong for the Rapid side, now coached by Mircea Lucescu’s son Răzvan. The Dutch were beaten at Giulești and Rapid progressed to the group stage for the first time, where Rennes, Shakhtar and PAOK were duly overcome. Then followed Hertha Berlin and Hamburg – both flying high in the Bundesliga – in the knock-out rounds. But in the quarter-final, Rapid faced a more familiar obstacle: Steaua.

Amid great excitement among Romanian football fans at being guaranteed a European semi-finalist for the first time since 1989, these old enemies played out two tense draws: 1-1 at Giulesti and 0-0 at Ghencea. Steaua thus progressed on away goals – only to be knocked out by Middlesbrough in the semi. Not content with dumping them out of Europe, Steaua pipped Rapid to the league that season as well. This was to prove the beginning of the end for the railwaymen.

CSA Steaua vs Academia Rapid at National Arena (Futbolgrad Network/Tim Appleton)

Two more top-four finishes followed, and some more European ventures, including another sally into the group stage, but soon financial difficulties kicked in, partly related to the owner’s legal problems. Copos, under investigation for corruption, was photographed sadly turning out his empty pockets. The team struggled in mid-table while a series of provincial clubs like CFR Cluj, FC Timișoara, Oțelul Galați, Unirea Urziceni and Vaslui made most of the running in the late 2000s. In November 2012, Rapid filed for insolvency. At the end of the season, in spite of finishing eighth, they were refused a Liga 1 licence and administratively relegated. However, the incompetent football federation had messed up in an unsuccessful attempt to expel Universitatea Cluj too and found themselves with an odd number of teams in the league. So in July, they organised a one-off match between Rapid and Concordia Chiajna to determine who would take the extra place, to return the league to an even number. Rapid won the play-off, but their opponents appealed to the Court of Arbitration for Sport and, two weeks before the start of the season, had the decision overturned.

Phoenix clubs and rebuild

Copos sold the club that summer. Rapid bounced straight back to the top flight under former Romania striker Viorel Moldovan but were demoted again the next season – on the field this time. It proved the fatal blow. In the 2015-16 season the team battled away in front of small crowds in Liga 2 and won promotion under the guidance of former midfielder Dan Alexa, but there was no more money. Players went unpaid for months on end, and debt repayments were not met. One day before the season kicked off in July 2016; the club was dissolved.

The following month, two phoenix clubs were founded and registered in Liga 5, the lowest level in the senior football structure. (Below the national Liga 3, each of the 42 counties in Romania runs its own amateur Liga 4 and, if there is demand, Liga 5.) AFC Rapid fielded a youth team from the defunct old club and won the division, ahead of the other new Rapid-connected team, which also won promotion. In the summer of 2017, however, the earth began to shift. The mayor of Bucharest’s Sector 1 got together with three ex-Rapid players – the bona fide legends Daniel Pancu and Daniel Niculae, plus midfielder-turned-aspiring businessman Ovidiu Burcă – to form a new club. The name would be Academia Rapid since the name ”FC Rapid București” would remain unavailable until the old club’s commercial property was put up for auction. Pancu, 39, and Niculae, 34, could boast 66 caps between them, not to mention having each won a league and a cup with Rapid in separate spells at the old club. They would play as well as functioning as club presidents. Another former team-mate, Constantin Schumacher, 41, would coach the team. The club would compete in the amateur Liga 4.

All was hunky-dory. Apart from not having the rights to the name or history of the old Rapid. And the awkward fact that another powerful club improbably happened to be in the same division. The army had just founded a new entity, CSA Steaua, after successful litigation against Steaua owner Gigi Becali gave them back the rights to the name and history of the 1986 European champions. (Becali was, embarrassingly, forced to rename his club FCSB, but they retained their top-flight place.) CSA were well-funded for this level – although much less so than Academia – and had a superior youth set-up. Their sporting director was Steaua and Romania legend Marius Lăcătuș. They had a loyal fan-base, made up of various ultras groups who had become disillusioned with Becali’s running of Steaua over the years. They would be tough opponents.

We need hardly mention that no Liga 4 line-up had ever been stronger, or generated more interest. The division was from the start a two-horse race. In four titanic head-to-heads Rapid prevailed, winning three and drawing one, securing in the process a place both in the promotion play-off to Liga 3 and in the national phase of the Romanian Cup for 2018-19. Huge crowds attended these games: the 36,000 who turned up in April at the National Arena, which CSA hired because their little ground only held around a thousand, made it the best-attended match in Romania all year (that includes internationals and FCSB’s UEFA Cup match against Lazio). These fourth-division fans, drawn in by chance to see some old heroes in action and engage in some harmless banter and violence, reignited a football scene which, throughout the country, appeared to be on its last legs. Endemic corruption and match-fixing, coupled with an apparent reluctance to render the product attractive to consumers, had eroded public interest in football for many years. Average attendances had halved in a decade, dozens of big clubs had gone out of business. For one ridiculous season, Academia Rapid and its fans reminded the moribund top two divisions of what football can be: a communion between supporters and players; the expression of shared values on the pitch and in the stands; the simple joy of songs, flags and firecrackers.

Perhaps we went overboard.

Rapid – What will the future hold?

In autumn 2018, Academia Rapid changed its name to FC Rapid, having bought the brand at auction for around 400,000 euros. They are currently top of their regional series of the third division: if they stay there Liga 2 beckons. So far, so good. However, behind the scenes, things are not so rosy. Niculae, captain, top scorer and best player for most of last season, resigned during the summer of 2018 after a disagreement over the direction of the club, falling out with Pancu in the process. He was concerned that not enough emphasis was being placed on youth development, and that the club was being less than transparent about its finances and decision-making. Coach Schumacher was sacked in September after the club’s first defeat since its re-foundation, replaced on the bench by Pancu. Niculae’s successor as captain and linchpin, 37-year-old Vasile Maftei, who had skippered Rapid on the 2005-06 “Uefantastic” adventure, quit in disgust. He had joined only the previous winter from top-flight Voluntari, attracted by the enthusiasm of his old team-mates.

Giulesti railway view (Tim Appleton/Futbolgrad Network)

Last month the Giulești stadium, built in the 1930s backing onto the railway tracks, hosted its last ever fixture before redevelopment ahead of Bucharest hosting games at Euro 2020. The 41-year-old Pancu fulfilled his promise that his swansong as a player would coincide with the ground’s final match. This totemic figure, beloved by the fans since signing for the club as a teenager in 1996, rounded off his sixth (!) spell as a Rapid player with a stiff-backed five-minute cameo at the end of a desperately poor 1-0 win over a mid-table side from a small village on the bank of the Danube. The spectacular scissor-kick into the top corner that would have sent off both player and stadium in memorable fashion eluded him, but at the end of the game, nobody was leaving. The floodlights were switched off, Pancu knelt in homage before the packed stands, and highlights of the Giulești story were replayed on a temporary screen. The goals from great European nights past received rapturous cheers all over again. “Pancone”, a man so old he scored for the club in the Cup-Winners’ Cup, attended to the ritual of leading the ultras’ chants in the peluza. Then it all went quiet, and the fans began to file out into the darkness, some keeping a plastic seat as a memento. And this most atmospheric of football venues, after eighty years, passed into history.

Since the departures of Niculae, Schumacher and Maftei, Burcă and Pancu are all that remains of the founding rapidistii, although Iencsi is now working with the youth team. The ultimate source of the club’s funding is still obscure, and its links with the unpopular ruling PSD party cause discomfort among certain fans. The club will spend a year and a half exiled from its home ground, and on-field performances have been lacklustre lately. Recent aggression towards the Facebook pages of critical fan groups has also attracted ire. Could we be close to another crisis point?

Besides AFC Rapid, which still struggles on, penniless and homeless, in the fourth tier, a new, fan-owned club is now active in Liga 5. ACS Frumoșii Nebuni ai Giuleștiului, or “the Beautiful Madmen of Giulești”, is a group of ultras who are all chipping in to run their club as something akin to a community association. They have played several matches at Giulești, in spite of only attracting a hundred or so spectators; they ask for donations instead of charging a ticket price, they have a better range of merchandise than the Liga 3 Rapid; they even launched their own craft beer in October 2018. Support for these minnows does not appear to be growing in terms of bums on seats: people are still more attracted to Pancu’s boys, who have money and therefore a realistic chance of returning to the big time. But who knows? Perhaps before too long fans will turn away from the dubious corporate business, with its team stripped of most of its heroes, and examine what it was that made Rapid București so special.

Tim Appleton is the owner of the blog romaniaballs.wordpress.com and can be found on Twitter @romaniaballs

COMMENTS

Excellent read. I reckon you forgot to mention how bitterly cold that last game was…

Most atmospheric = most likely to collapse during ‘Pancu Italiano’?

Will miss it though, especially the pitch black stairwell…